How to write 90% cleaner code with Hooks 🎣

December 07, 2018• ☕️ 4 min read

The year 2018 brought a lot of new features into the React Ecosystem. The addition of these features is helping developers to focus more on user experience rather than spending time writing code logic.

It seems that React is investing more towards a functional programming paradigm, in a search of great tools for building a UI which is more robust and scalable.

Recently, at ReactConf October 2018, React announced a proposal API called Hooks which took the community by storm. Since then developers are exploring and doing experiments with them and it has received a great feedback in the RFC (Requests for comments).

This article is my attempt to explain:

Why hooks were introduced

How can we prepare ourselves for this API

How can we write 90% cleaner code by using React Hooks 🎣

If you just want to have a feel of this new API first, I have created a demo to play with. Otherwise, let’s get started by looking at 3 major problems we are facing as of now:

1. Reusing Code Logic

You all know that reusing code logic is hard and it requires a fair bit of experience to get your head around. When I started learning React about two years ago, I used to create class components to encapsulate all my logic. And when it comes to sharing the logic across different components I would simply create a similar looking component which would render a different UI. But that was not good. I was violating the DRY principle and ideally was not reusing the logic.

The Old Way

Slowly, I learned about HOC pattern which allowed me to use functional programming for reusing my code logic. HOC is nothing but a simple higher order function which takes another component(dumb) and returns a new enhanced component. This enhanced component will encapsulate your logic.

A higher order function is a function that takes a function as an argument, or returns a function.

export default function HOC(WrappedComponent){

return class EnhancedComponent extends Component {

/*

Encapsulate your logic here...

*/

// render the UI using Wrapped Component

render(){

return <WrappedComponent {...this.props} {...this.state} />

}

}

// You have to statically create your

// new Enchanced component before using it

const EnhancedComponent = HOC(someDumbComponent);

// And then use it as Normal component

<EnhancedComponent />

Then we moved into the trend of passing function as props which marks the rise of the render props pattern. Render prop is a powerful pattern where “rendering controller” is in your hands. This facilitates the inversion of control(IoC) design principle. The React documentation describes it as a technique for sharing code between components using a prop whose value is a function.

A component with a render prop takes a function that returns a React element and calls it instead of implementing its own render logic.

In simple words, you create a class component to encapsulate your logic (side effects) and when it comes to render, this component simply calls your function by passing only the data which is required to render the UI.

export default class RenderProps extends Component {

/*

Encapsulate your logic here...

*/

render(){

// call the functional props by passing the data required to render UI

return this.props.render(this.state);

}

}

// Use it to draw whatever UI you want. Control is in your hand (IoC)

<RenderProps render={data => <SomeUI {...data} /> } />

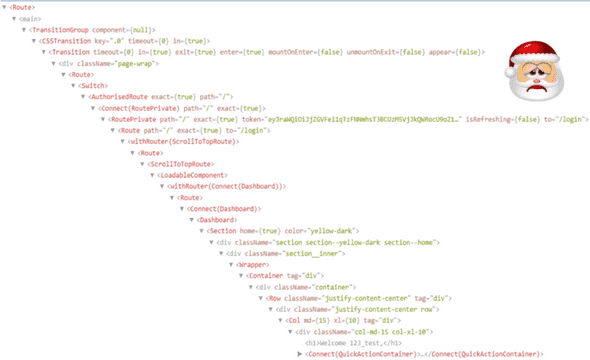

Even though both of these patterns were resolving the reusing code logic issues, they left us with a wrapper hell problem as shown below:

So, to sum it up we can see there are few problems associated with reusing code logic:

- Not very intuitive to implement

- Lots of code

- Wrapper hell

2. Giant Components

Components are the basic unit of code reuse in React. When we have to abstract more than one behaviour into our class component, it tends to grow in size and becomes hard to maintain.

A class should have one and only one reason to change, meaning that a class should have only one job.

By looking at the code example below we can deduce the following:

export default class GiantComponent extends Component {

componentDidMount(){

//side effects

this.makeRequest();

document.addEventListener('...');

this.timerId = startTimer();

// more ...

}

componentdidUpdate(prevProps){

// extra logic here

}

componentWillUnmount(){

// clear all the side effects

clearInterval(this.timerId);

document.removeEventListener('...');

this.cancelRequest();

}

render(){ return <UI />; }

- Code is spread across different life cycle hooks

- No single responsibility

- Hard to test

3. Classess are Hard for Humans and Machines

Looking at the human side of the problem, we all once tripped trying to call a function inside a child component and it says:

TypeError: Cannot read property 'setState' of undefined

and then scratched our head trying to figure out the cause: that you have forgotten to bind it in the constructor. So, this remains the topic of confusion even among some experienced developers. I have written a separate article to discuss more about this. If you interested, give it a read.

this gets the value of object who invokes the function

Also, you need to write lots of boilerplate code to even start implementing the first side effect:

extends -> state -> componentDidMount -> componentWillUnmount -> render -> return

Classes are also hard for machines for the following reasons:

- Minified version won’t minify method names

- Unused methods won’t get stripped out

- Difficult with hot reloading and compiler optimisation

All the three problems we discussed above are not three distinct problems but these are symptoms of one single problem and that is React has no stateful primitive simpler than class component.

With the advent of the new React Hooks proposal API, we can solve this problem by abstracting our logic completely outside of our component. In fewer words, you can hook a stateful logic into the functional component.

React Hooks allow you to use state and other React features without writing a class.

Let’s see that in the code example below:

import React, { useState } from 'react';

export default function MouseTracker() {

// useState accepts initial state and you can use multiple useState call

const [mouseX, setMouseX] = useState(25);

const [mouseY, setMouseY] = useState(25);

return (

<div>

mouseX: {mouseX}, mouseY: {mouseY}

</div>

);

}

A call to useState hook returns a pair of values: the current state and a function that updates it. In our case, the current state value is mouseX and setter function is setMouseX. If you pass an argument to useState, that becomes the initial state of your component.

Now, the question is where do we call setMouseX. Calling it below the useState hook will cause an error. It will be the same as calling this.setState inside render function of class components.

So, the answer is that React also provides a placeholder hook called useEffect for performing all side effects.

import React, { useState } from 'react';

export default function MouseTracker() {

// useState accepts initial state and you can use multiple useState call

const [mouseX, setMouseX] = useState(25);

const [mouseY, setMouseY] = useState(25);

function handler(event) {

const { clientX, clientY } = event;

setMouseX(clientX);

setMouseY(clientY);

}

useEffect(() => {

// side effect

window.addEventListener('mousemove', handler);

// Every effect may return a function that cleans up after it

return () => window.removeEventListener('mousemove', handler);

}, []);

return (

<div>

mouseX: {mouseX}, mouseY: {mouseY}

</div>

);

}

This effect will be called both after the first render and after every update. You can also return an optional function which becomes a cleanup mechanism. This lets us keep the logic for adding and removing subscriptions close to each other.

The second argument to useEffect call is an optional array . Your effect will only re-run when the element value inside the array changes. Think of this as how shouldComponentUpdate works. If you want to run an effect and clean it up only once (on mount and unmount), you can pass an empty array ([]) as a second argument. This tells React that your effect doesn’t depend on any values from props or state, so it never needs to re-run. This is close to the familiar mental model of componentDidMount and componentWillUnmount.

But isn’t our MouseTracker component still holding the logic inside? What if another component wants to share mousemove behaviour as well? Also, adding one more effect (e.g window resize) would make it little hard to manage and we are back to the same problem as we saw in class components.

Now, the real magic is you can create your custom hooks outside of your function component. It is similar to keeping the logic abstracted to a separate module and share it across different components. Let see that in action.

// you can write your custom hooks in this file

import { useState, useEffect } from 'react';

export function useMouseLocation() {

const [mouseX, setMouseX] = useState(25);

const [mouseY, setMouseY] = useState(25);

function handler(event) {

const { clientX, clientY } = event;

setMouseX(clientX);

setMouseY(clientY);

}

useEffect(() => {

window.addEventListener('mousemove', handler);

return () => window.removeEventListener('mousemove', handler);

}, []);

return [mouseX, mouseY];

}

And now we can clean up our MouseTracker component code (90%) to a newer version as shown below:

import React from 'react';

import { useMouseLocation } from 'customHooks.js';

export default function MouseTracker() {

// using our custom hook

const [mouseX, mouseY] = useMouseLocation();

return (

<div>

mouseX: {mouseX}, mouseY: {mouseY}

</div>

);

}

That’s kind of a “Eureka” moment! Isn’t it?

But before settling down and singing praises of React Hooks, let’s see what rules we should be aware of.

Rules of Hooks

- Only call hooks at the top level

- Can’t use hooks inside class component

Explaining these rules are beyond the scope of this article. If you’re curious, I would recommend reading React docs and this article by Rudi Yardley.

React also has released an ESLint plugin called eslint-plugin-react-hooks that enforces these two rules. You can add this to your project by running:

npm install eslint-plugin-react-hooks@next

This article was part of my talk at the ReactSydney meetup December, 2018. I hope this article has intrigued you to give React hooks a try. React 16.8.0 is the first release to support Hooks. I am super excited about the React roadmap which looks very promising and has the potential to change the way we use React currently.

You can find the source code and demo at this link.

Hope you’ve enjoyed reading this article. There’s more to come 😃.

Written by Amandeep Singh. Developer @ Avarni Sydney. Tech enthusiast and a pragmatic programmer.